Millions play the UK’s National Lottery. Few win. In fact for every pound spent on the lottery its reckoned players get about 50p back. Since players lose money on every ticket on average, playing the lottery is not a rational use of hard earned cash. Nor is gambling. But, are those hours spent dreaming of what might be done with a couple of million worth a quid or two, or does thinking about how to spend the £90,000 that wild accumulator promises if it comes in worth the 50p it cost to put on? Economics, traditionally, would say no. I am not so sure, assuming either activity does not become a problem and the money won’t be missed at all.

I have gone off topic. What I want to do in this article is compare playing the lottery to investing in the UK stock market, specifically the FTSE All-Share, in terms of wealth creation. I think if you play the lottery, then spending a bit on the Wednesday and Saturday draws makes less sense than going all in on one draw at least frequent intervals. So, I am going to assume our players spend £50 a month but they stick it all on one draw a month by buying 25 tickets in it. The same amount will be invested in the FTSE All-Share. Both the investors and the lottery players will invest or play for 25 years. We will get to the investing side a bit later, so let’s deal with the lottery first.

National Lottery

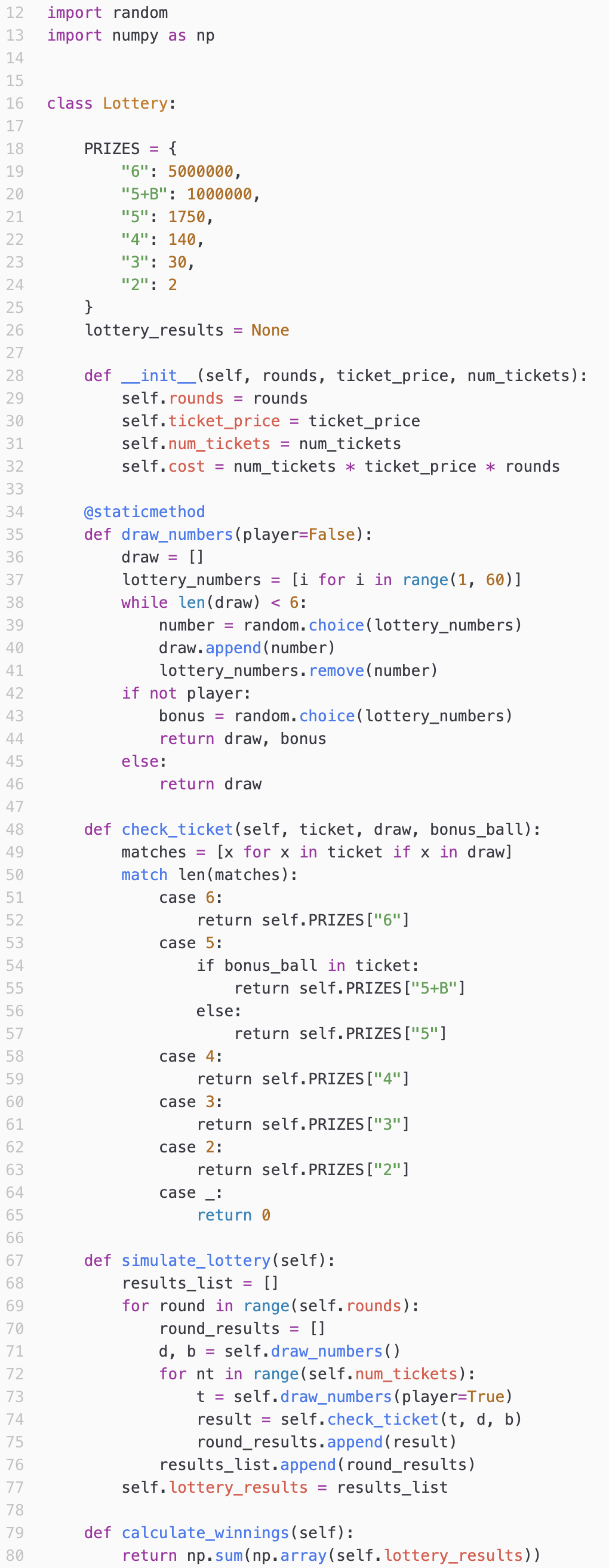

I used Python to simulate playing the lottery, by making a class called Lottery that handles setting up a random draw with a bonus ball, handling multiple lucky dip tickets and checking if there are any winners. As for prizes I took what I could find for averages from the National Lottery website. Now the £5m jackpot prize was somewhat arbitrary. I could find the maximum jackpot won, minimum jackpot won, something called an average maximum jackpot and an expected minimum, none of which were helpful, and multiple tickets can win the jackpot complicating things. So I went for £5m which is above the expected minimum jackpot of £3m (or £2m if its a midweek draw) but below the £13m stated for the average maximum jackpot.

What I did was simulate 10,000 people playing this lottery once a month for for 25 years (300 months). Each time they play they buy 25 tickets at £2 each. Thats £15,000 worth of lottery tickets, and the majority of our players are going to be disappointed. The average player lost money, as 9,986 of them made no more than £9,912 over the course of the 25 years, and once you take of the cost of buying tickets off that amount its a loss of £5,088.

However, 14 of them actually made a profit. And it was a big one. We had one jackpot win and a 13 other £1m prizes. But, they represent 0.14% of the 10,000: the other 99.86% people lost money. And think about how many attempts were made: 10,000 playing 300 times is 3 million attempts. With 25 tickets being bought per try thats 75m tickets, so we should have expected to see a jackpot winner or two based on the odds, and also 10 or so matching five and a bonus ball, so the simulation looks to be on the money.

| Prize Category | Odds of Winning | Prize Value |

| Match 6 | 1 in 45,057,474 | Jackpot |

| Match 5 + Bonus Ball | 1 in 7,509,579 | £1,000,000 |

| Match 5 | 1 in 144,415 | £1,750 |

Running a lottery is a good business. Players spent £150m on tickets. The average player won around £5,000, and there were 9,986 of them, so thats £49.93m and then we had those 14 winning £18m between them. Overall then thats about £67.93m in prizes paid out. The lottery runners pocketed £82.04m to run their business, donate to good causes and pay the tax man, and perhaps leave a little something left over for the shareholders.

Investing in the stock market

One way to do this would be to assume that the past will look like the future. Back in January 1999 the FTSE All-Share total return index was at 2,477 and today its around 8,772. It has compounded by about 0.42% each month. We could take £50, grow it by 0.42%, add another £50 and grow the total by £50 and so on. After 300 months you end up with £30,129. That’s not too bad, considering the total investment of £15,000. Sure, we haven’t made a millionaire, but our investor has doubled their money and certainly not lost anything.

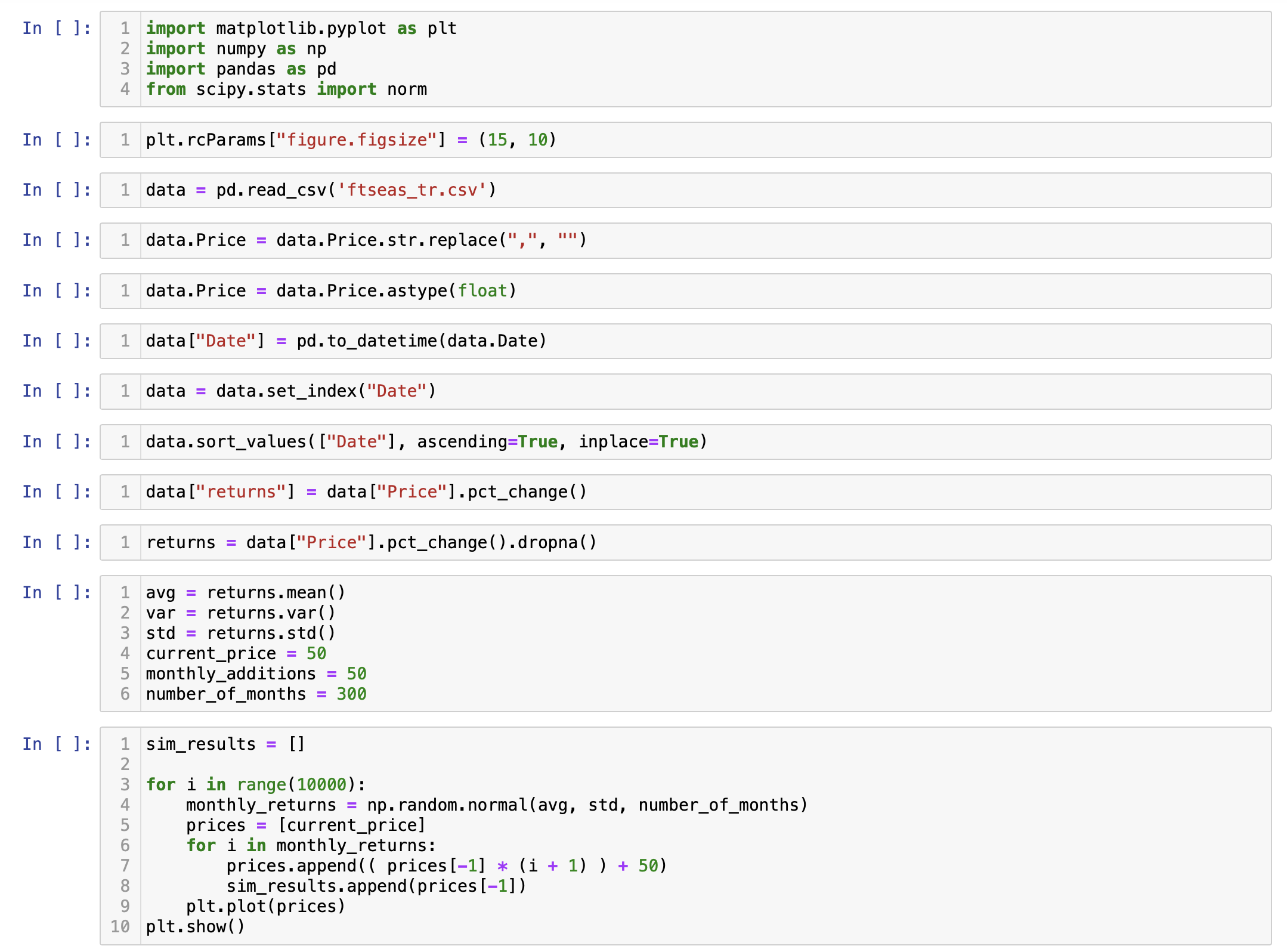

But the stock market is risky. This example assume no risk. So, we can add an element of luck. If we look fat all the monthly returns over the last 25 years then the FTSE All-Share total return index (that includes dividends) has an average monthly return of 0.51% with a standard deviation of 3.94%. The mean and standard deviation can be used to simulate what investing £50 a month in the FTSE All-Share might yield after 25 years. Here is the code I used to run 10,000 simulations of what investing in this index might look like.

What this code does is generate 300 separate random variables representing our returns over the quarter century from a normal distribution with mean 0.51% and standard deviation 3.94%. It is assumed that returns are normally distributed. A starting value of £50 gets the first random return applied, then fifty pounds is added and the next return is applied and so on.

The results are better on average than playing the National Lottery. The average investor ended up with £13,400. Considering they invested £15,000, thats not a great return, in fact they have made a loss. But 99.86% lottery players lost at least £5,088. The median was £10,167. so we have some skew here, and that skew is due to some large gains—the highest of which was £183,815—which are dragging the mean average to the right of the median. But at the extreme left, we have an investor who ended up with £93 and presumably fuming after investing £15,000.

the 66th percentile of the simulated investment yield is £15,116. So, we do have 33% of investors who have at least broken even or made some money and at least 10% of which have almost doubled their money (the 90th percentile is £29,079).

The stock market is a lottery

These simulations are sobering. On the one hand they demonstrate quite clearly that wining the lottery is unlikely, and most people, 99.86% in fact, lose money. But, investing in the stock market is not a certain path to riches either as it is risky. Perhaps my modelling is flawed, and I will review it, but what we can learn from this is that the overwhelming majority of people will lose money playing the lottery. I don’t think that will surprise anyone.

But, the stock market is a surprise. The numbers haven’t been fudged, they are drawn from real world FTSE All-Share monthly data. And assuming that returns are normally distributed (they are not, fat tails and the like complicate things) using the mean and standard deviation of the monthly returns generated the data described in the 10,000 simulations. And what is shows is that most, albeit a lower proportion, lost money in the markets. But a greater proportion ended up breaking even or wealthier, although, we didn’t mint any millionaires in the process.

Although past performance is not a guide to future performance, it is worth saying that investing in the FTSE All-Share (and reinvesting dividends) 25 years ago would have resulted in a 254% gain. I think many will attest that having played the lottery for the same amount of time they are not any richer at all. I for one will continue to invest in the markets. Perhaps I have more faith in achieving a return than the simulation suggests, perhaps I overate my stock picking ability. But, if the last 25 years are anything to go by, and even if the simulation results are not inspiring, I can conclude that I would in all probability I would be better off investing in the UK stock market compared to playing the lottery.

But I will also occasionally have a punt on the lottery. See, although rationally it doesn’t make sense, and the odds are stacked against you, and for every £2 ticket you are very, very unlikely to see that money again, perhaps the minutes or hours spent daydreaming about what could be done with those millions is worth the entry price. Thats something that economists don’t usually consider.