The Chartered Financial Analyst Institute (CFAI) defines 15 biases that might affect investors, analysts, retail traders, or basically anyone involved in the stock markets or finance in general. The 15 biases are broken up into nine cognitive errors and six emotional biases. The cognitive errors are further divided into five problems with belief perseverance and four information-processing errors.

A future post will cover the cognitive errors. In this post I will take a look at the six emotional biases:

- Loss aversion

- Overconfidence

- Self-control

- Status quo

- Endowment

- Regret aversion

Let’s have a look at each one of these in turn.

Loss aversion bias

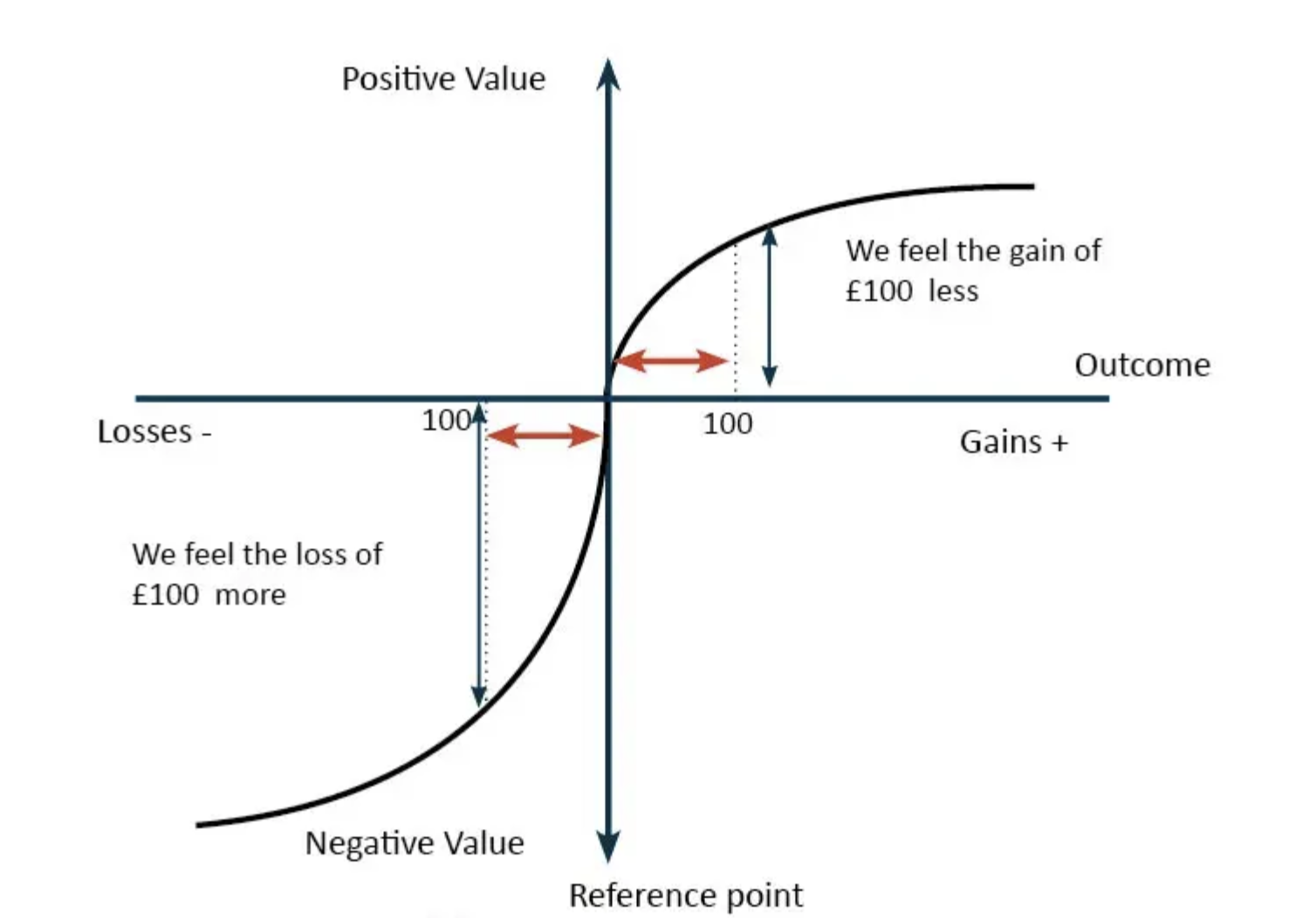

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize winning economist, and Amos Tversky (Nobel’s are unfortunately not awarded posthumously) posed a scenario to their students. A coin was to be flipped. If it came up tails they would lose and owe him $10. How, much would they need to win on heads to take this bet? The answer was around $20. They wanted twice as much upside compared to downside what is a 50:50 bet.

The observation was that people tend to feel the pain of a loss more strongly than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. There is an asymmetric valuation of gains and losses compared to some reference point. All this was stated more formally in Kahneman and Tversky’s work on loss aversion and prospect theory.

Holding on to losers and cutting winners early is where this particularly pernicious bias comes into play. A stock that is down 50% is held because it might come back. A position that is up 25% gets closed because it might turn around. Trading and investing is not about being right all the time. It’s about being really right when you are right, and when wrong, being wrong just a little. Loss aversion will turn that on its head as winners are cut soon and losers cut late, in what has also been described as the disposition effect.

Overconfidence bias

People tend to overestimate their own abilities. Ask anyone if they are a good driver, which by definition means above average, and they will probably say yes. That cannot be true though can it? If almost everyone is above average then they are all average, right? Furthermore, they often believe that others would not rate them as highly.

Psychological scientists Roy and Liersch found that although people tend to rate themselves as above average they also believe that others would not rate them as highly as they rate themselves. So it’s the rest of the world that is wrong and not the individual? Sure.

In investing, overconfidence is likely to reveal itself as overestimating returns and underestimating risks. Furthermore, confidence in positive outcomes are overstated. Together this type of behaviour is called the illusion of knowledge. Overconfident investors often trade excessively, incurring hefty transaction costs. This situation is compounded by the self-attribution or serving bias. Successful outcomes are attributed to the skills of the individual. Failures, however, are because of other people or things acting to subvert our best laid plans.

There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know and those who don’t know they don’t know

John Kenneth Gailbraith

But there is a way out of the cycle. The Dunning-Kruger effect describes the phenomenon whereby people will low ability, expertise and limited time in the field tend to overestimate their ability or knowledge*. As time passes, they tend to decrease their confidence, as they realise how much they don’t know. Perhaps they have a car crash, or a close call. Eventually, when expertise actually build the confidence rises again, perhaps this time deservedly so.

Keeping a journal of the reasons for exerting every position, successful or not should help define just how confident we should be as investors and suggest ways in which improvements can be made. It should show quite clearly where we are on the scale of novice to expert. And, keeping a diversified portfolio, and not allowing our overconfidence to lead to oversized bets on individual positions, might just prevent a ruinous outcome whilst we are building out expertise.

*As an aside I strayed away from saying experience here. You can have all the experience in the world at doing something poorly time and time again. Experience has to lead to expertise or its not worth much.

Self-control bias

The goal of investing, in a nutshell, is delaying gratification today for, hopefully, bigger rewards in the future. The problem is that people are not very good at cutting their current consumption down today and saving money for the future. Hence, governments direct employers to take a slice of their employees pay checks and direct it into pension plans.

The concept of interest is, at least in part, a response to the problem of delayed gratification. I could spend this £100 now and do or buy something nice for myself. But, I could lend it to you and get it back in a year, and do the nice thing then. But, I would have to wait for my enjoyment, so it makes sense that I should get more back to buy myself something even nicer in compensation.

But, people seem inclined to take the wrong side of the interest trade, borrowing more and more to fund their need for current gratification. Also, they don’t save enough now, and end up later in a bind, having to perhaps take a lot of risk in hope of catching up.

Status quo bias

The status quo bias is a cognitive bias that refers to the tendency of people to prefer things to stay the way they are, rather than to change. This bias can be seen in a variety of contexts, from politics and public policy to personal decision-making. Essentially, the status quo bias represents a preference for the current state of affairs, often regardless of whether or not that state is optimal or desirable.

One area where the status quo bias is particularly pronounced is in investing. Investors often exhibit a strong preference for the current state of their portfolio, and may be reluctant to make changes even when market conditions change or new investment opportunities arise. This can lead to suboptimal investment decisions, as investors may hold onto losing positions for too long or miss out on potential gains by failing to adapt to changing market conditions.

For example, an investor may hold onto a stock that has been performing poorly for months or even years, simply because they are comfortable with the current state of their portfolio and do not want to make changes. Despite evidence that the stock is unlikely to recover, the investor may continue to hold onto it out of a desire to maintain the status quo, rather than to take a more proactive approach to managing their investments. Over time, this can result in significant losses and missed opportunities for growth.

Endowment bias

Think of something you own and cherish. For me it’s a particular guitar. Now go on your preferred electronic market place and see what that particular something is selling for. Chances are you won’t agree with the prices seen. They will be two low. This is the endowment effect in action.

Now, there might be good reasons for the price discrepancy. Perhaps your item is newer, in better condition. But, often there is not. It is sentiment that causes the price of your cherished item to be higher than what others are willing to pay for it. It does not hold sentimental value for them, at least not yet.

In investing, endowment effect is not about holding onto losers in a portfolio. That’s is loss aversion. Its about holding onto shares in companies you just like or are familiar with long beyond when they should have been sold. Perhaps, they were gifts from family members. Perhaps an investor would feel somehow disloyal if they sold them. It can mean that a portfolio has an unsuitable asset allocation or risk profile.

For those affected, treating stocks as things you rent rather than own can do the trick. Ask if you had the money again, would you buy this stock today? Covering up the name of the stock and looking at its price chart tor summary financials can also help.

Regret-aversion bias

Remember those COVID-19 era meme stocks? A lot of people got rich on the back of their soaring prices. A lot of people lost a load of money as they crashed back down to earth. Why were people so keen to following the herd without considering if they were making a bad decision to being led astray. I suggest fear or missing out or regret-aversion was the emotional bias that led to the herding mentality.

But its not always about taking on excessive risks with little consideration. It could be that an investor invests in low-yield government bonds, terrified of stock market volatility, but that yield is not enough to meet their investment long-term objectives.

Identifying emotional biases

Before we can deal with our emotional biases we have to find out which ones we have. So here are some questions, that should be answered honestly.

- Question one: You have narrowed your investment choice to two companies. One is a well-known, and you have seen a lot of people getting very excited about its potential returns. The other is not popular at all, and hardly anyone is mentioning it but operationally seems exactly the same as the first. Which one do you invest in?

- Question two: You make an investment and it drops 30% in the first three months. According to analyst reports and the financial news you have read, there are real problems at the company. What do you do?

- Question three: How easy do you think it was to predict the global stock market crash due to the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020?

- Question four: How much do you think your peers have saved for retirement as a percentage of their current earnings, do you think you are saving more less than them?

- Question five: Before you are two stock charts. One is clearly going up the other is going sideways. Which one would you prefer to invest in? Now I tell you that the one going sideways is actually a stock you own, the other is for a similar stock that you don’t. Are you making any changes to your portfolio knowing this?

- Question six: You have multiple defined contribution pension plans. When you get the annual report for one you see that you are invested in the index stalwarts fund. There are two other funds available, patient capital and hyper growth winners. What do you do?

What emotional biases do you think these questions are designed to reveal?

Story and meme stocks

I was not surprised at the meteoric rise (and fall) of so-called (perhaps pejoratively) meme stocks during the pandemic. I think regret aversion explains the situation quite nicely for the way up, and then again perhaps with a bit of loss aversion on the way down.

But then there are story stocks. Facebook once upon a time was one. Amazon also. There will be new ones. This sort of stock is headed up by a charismatic (in their own way) leader with a vision, that is able to attract tons of cheap capital to fuel the loss making in pursuit of some grand end goal far in the future. There will be a mission statement and a succinct tag line that would make your spine crawl out the door we’re you not caught up in the story.

And it’s hard to not get caught up in a good story. We humans are natural storytellers and are often the hero of our own one. We crave stories and gobble them up. The trouble is when they are particularly captivating we tend to twist facts to suit the story if they don’t support the full narrative. So, there exists a sort of narrative bias that the other emotional biases don’t cover. And we are particularly prone to it when a stock has a real page-turner of a story behind it.

1 Comment